Final evaluation events on the 15th of November and on the 6th of December 2019 in Kossuth Club – with access to the winner video-clips!

Photos on site at venue: Tamás Thaler

Archduke Franz Ferdinánd is conducting inspection of the troops in the vicinity of Sarajevo before his assassination in June

Brest-Litovsk and Versailles versus Trianon and Rapallo: Are we Miklós Horthy’s soldiers? *[1]

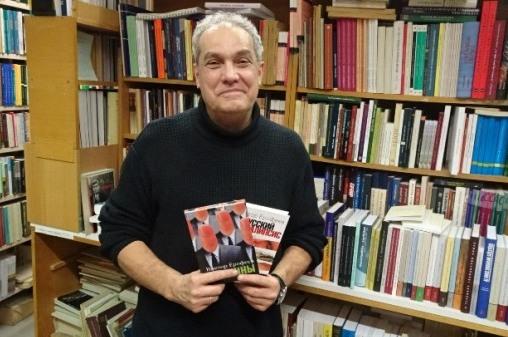

Géza Gecse Project Director started the meeting organized by Aspektus on November 15, 2019 at the Kossuth Club in Budapest by saying that the deadline for the short clip competition had been extended by popular demand.

He also said that the reason for giving such a long title to the closing event was in part because the contemporaries taking part in the negotiations referred to the continuity of the international agreement of March 3rd , 1918 in Brest-Litovsk and that of April 16th, 1922 in Rapallo, at least in a certain analogy; and also in part it shows the failure in conduct which both parties, i.e. Soviet Russia and Germany, demonstrated by the end of the war when Europe was still the cultural and economic center of the world. The territory disannexed from Russia, the first defeated nation of World War I, in Brest-Litovsk was as large as Germany herself at approximately 1 million square kilometers.

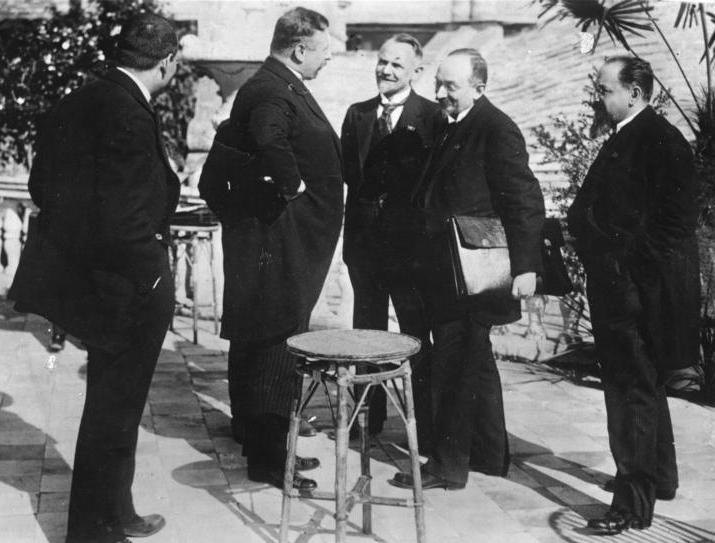

Kamenev heading the Soviet delegation arrives at Brest-Litovsk

From a military standpoint, Germany was completely disarmed at Versailles. While her neighbors like Poland could have 600 000 soldiers and France 700 000 soldiers in arms in peacetime, Germany’s number was limited to 100 000.

From a territorial standpoint, the Treaty of Saint-Germain as a dictated peace signed with Austria also 100 years ago, which ceded three-fourths of the country, was even worse than the Treaty of Trianon for Hungary. From an ethnic minority perspective, such homogeneous German territories came under Italian, and in particular Czechoslovak jurisdiction, which had no business being there. It would have been quite easy to work out a solution in which they could have remained in Austria or would have been annexed to Germany. Thus a complete mockery was made of the right to national sovereignty in the name of which the entire conference took place on the outskirts of Paris in January 1919: not only was Austria not allowed to unite with Germany, but neither was the name of German-Austria permitted. Austria was allowed essentially the same, moreover even smaller force than Hungary, a skeleton of an armed force of merely 30 000 soldiers. Although given the circumstances this was not a serious threat, even the possibility of a union with Hungary was forbidden.

For Germany, the Treaty of Versailles signed one hundred years ago on June 28th was not nearly as severe in terms of territory, but in economic terms it imposed a far greater burden than the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and the exact scope of the reparations imposed by it were impossible to reach an agreement on for years.

Below is a link to the summary of all that the closure of World War I meant with the invited speakers in Hungarian. The content of it is summed up in the following article in English:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=62-4hvUCFAA(külső hivatkozás)

Miklós Horthy on the Great Hungarian plain in 1923

The third important date which should not be overlooked is the centenary of Admiral Miklós Horthy’s march into Budapest.

Why didn’t the Horthy regime make a state memorial day of November 16th, as there is a footage of him ceremoniously entering Budapest?

Gábor Ujváry, Director General of the VERITAS Institute stated that although there are no written documents or otherwise proof, it is clear that Admiral Horthy’s march into Budapest on November 16th was strategic. Symbolic politics spans this period. The negotiations at Versailles began on January 18, 1919, the day on which the formation of the German Empire was declared in 1871. The Peace Treaty with the Germans was signed in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles on June 28th, exactly five years after Gavrilo Princip’s gunshots sounded in Sarajevo, told Gábor Ujváry.

From December 1918, the Károlyi and the Berinkey governments declared consistently all movements against them to be counterrevolutionary and therefore Horthy an his circle chose this day to enter the Hungarian capital, on purpose to distinguish the Horthy regime if not from the republic as a form of government, but at least from the form of government carried into effect by the Károlyi government.

László Gulyás, History Lecturer at the University of Szeged informed the audience of history conferences on the Horthy era every year in Szeged. There will be one also in this year. There are three possible dates from which one can date the beginning of the Horthy regime. The first one is August 13, 1919, when Miklós Horthy flies from Szeged to Siófok and becomes an independent political factor when the GHQ were sat up there. The second possible date is the march into Budapest on November 16, 1919. The third one, which was to manifest their law-abiding intentions, is March 1, 1920, when Horthy was elected Regent of Hungary. Certainly, a factor not making November 16th a National Day was that the left took to the streets at the same time and therefore they would have been commemorating the declaration of the republic a year earlier. Also, let us not forget that Horthy looked up to Franz Joseph, who avoided symbolic politics, as a role model. In addition, the White Terror cast a shadow on November 16th. When meeting with either the British representatives or the conservatives everyone asked whether or not there would be a White Terror or Jewish pogrom when Horthy marches into Budapest. It was for this reason that Horthy signed a promissory note before British diplomat Sir George Russell Clerk stating that there would not be such a problem.

Zoltán Tefner, History Lecturer at the Corvinus University stated that it should not be forgotten that in August 1919 the majority of Hungarian society saw the promise of consolidation in Miklós Horthy and for that reason the support base of the later Regent was far broader than today we generally think of it being. He had an army of a few thousand detachments, former officers who accompanied him from Szeged and with whom he had by that time occupied a part of Transdanubia. A few of the operations carried out by Prónay and Héjjas, however, triggered negative international reactions. But there were not only armed soldiers behind Horthy in August 1919 but also those figures whom we consider „Miklós Horthy’s soldiers”, who did not serve in the military. Moreover, until then, these people had never considered getting involved in politics.

Ottokár Prohászka

Zoltán Tefner directed the attention to Ottokár Prohászka, born in Érsekújvár (today Nové Zámky in Slovakia, an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary at that time), whose family was Catholic and ethnic German and Moravian. Prohászka was raised in Rome, in the Germanico-Hungarico College: he studied there for six years until he became a priest. It was encoded in his genes to keep clear of politics. He did not even possess the self-confidence for a political role but yet in 1906, he came to the conclusion that only Christian Socialism could save Hungary from total destruction. From then on he began to consider who would be the person capable of realizing a program of Hungary’s social uplift.

Horthy was the embodiment of this person for him in 1919, thus Prohászka joined the group of his committed followers. Few are aware of the fact that on March 1, in 1920 when Horthy was elected Regent by the National Assembly, it was Prohászka who went to pick up him by car from the Hotel Gellért. He led the delegation to the House of Parliament for Horthy to be elected as head of the Hungarian state. Later the Regent wanted to offer Prohászka the post of the PM, but that was a post the bishop would not accept. As a spokesman for the National Assembly Prohászka made incredibly sweeping speeches for nearly a month until he came to loathe doing this. He did not detect the same sort of strength in the National Assembly that he saw in Horthy himself. November 16th 1919 therefore held the message also that not only those could be „Miklós Horthy’s soldiers” who had been in the armed forces, but also those who did not support the new regime actively, only as silent partners.

Géza Gecse noted that it has been 101 years when it seemed all was lost. However, the Habsburg Monarchy’s and Germany’s troops were in enemy territory everywhere on the eastern front. Curiously enough, Gyula Gömbös suggested that the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy take command of the occupied territories on the eastern front.

As Gusztáv Gratz who worded the economic chapter for thee Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on the part of the Habsburg Monarchy, wrote after the war: by the end of August 1918, it was clear to them that the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy would not be able to survive economically past January 1919.

Gusztáv Gratz

Beside Ukraine, one of the key territories of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was Poland because during the course of the war, by the autumn of 1916 it became clear that it would be an independent nation. This is of vital importance for us Hungariansd because without an independent Poland there would have never been an independent Czechoslovakia nor an independent Yugoslavia.

Zoltán Tefner said that the Habsburg Monarchy had succeeded in alienating the Poles even before the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed when they invited (and note their wording here!) the Ukrainian People’s Republic to the negotiation table. Although by 1917 Hungary had not sunk yet into a serious provisions and supplies crisis, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy had on the whole. Charles IV and his Foreign Minister Ottokar Czernin had to secure wheat from somewhere. As a consequence, due to its catastrophic economic state, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy concluded a peace with the Ukrainians on February 9, 1918, referred to as the “Peace for Bread” (Brotfrieden).

Peace for Bread with Ukraine, February 9, 1918

Peace for Bread with Ukraine, February 9, 1918

In exchange, Ukraine was also awarded the territories east of Lublin in the vicinity of Chelm. This prompted such persons to abandon the Habsburg Monarchy whose loyalty to the dynasty had been unquestionable before.

Józef Haller

The Polish General Józef Haller, for example, escaped via Murmansk to Paris and from then on fought against the Central Powers on the side of the Entente. This situation remained the same until the start of the war with the Bolsheviks. In the summer of 1920, Hungary provided the Poles with weapons made by the Manfréd Weiss Steel and Metal Works, about the number of which one can read of huge numbers. As a result, the Red Army was unable to occupy Warsaw which was to Miklós Horthy’s credit as well. This fact most likely influenced the Poles who signed immediately the treaty with the Germans at Versailles, however, they were not as quick to sign the Treaty of Trianon with the Hungarians.

June 4, 1920. The Hungarian delegation on route to the Grand Trianon Palace

The situation changed of course when the war with the Bolsheviks came to an end but at the time the Hungarians were the only people the Poles could count on in the region.

Géza Gecse noted that two royal coups took place in 1921, one in March, the other in the autumn. The detachments, who were then playing an active role, were half Legitimists, i.e. Habsburg loyalists whilst the other half were anti-Legitimists, i.e. supported an independent Kingdom of Hungary free of any Habsburg relationship or influence. There was no difference, however, between these two factions concerning whether or not Sopron, the town in West of Hungary and its surroundings should remain part of Hungary and in fact, primarily as a result of their activity, this territory is part of Hungary to this day.

Pál Prónay

Just to mention a few names: Pál Prónay, Iván Héjjas, Gyula Ostenburg-Moravek, and Mihály Francia Kiss. In the following year, in 1922 both Germany and Soviet Russia (officially called RSFSR at that time) the two largest defeated European nations, were invited to Genova to a conference the purpose of which was to negotiate the economic reconstruction of Europe. The two defeated powers signed a zero option agreement amongst themselves and restored full diplomatic relations in Rapallo near Genova.

Miklós Bánffy

The newly appointed Miklós Bánffy, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Hungary was not idle either. On several occasions he met with Georgy Chicherin, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, to negotiate on initiating Hungarian-Soviet diplomatic relations; although, as he noted, there was no need for a peace treaty between the two countries because that had already been concluded in the city of Brest-Litovsk in 1918. Then in 1923 the French, who were not satisfied with the construction of German reparations, marched into the Ruhr region. Interestingly, in spite of the fact that they remained stationed there fully armed, and notwithstanding the fact that the Germans did not resist militarily, they got nowhere. A few months later they were forced to evacuate the territory.

The German and the Soviet delegations at Rapallo

According to Gábor Ujváry, the Rapallo Agreement in part resulted from the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Soviet-Russia was not invited to the negotiations at the Versailles Peace Conference, because she had made a separate peace at Brest-Litovsk. Géza Gecse noted that one should consider the failed negotiations at the Prince’s Islands (presently Adalar, Istanbul Province, Turkey), suggested by U.S. president Woodrow Wilson. What’s more, a Russian emigré government was formed in Paris just as with the Poles and the Czechoslovaks but there were also other reasons for the Russians not being present at the peace negotiations in 1919, such as the fact that various White Russian counterrevolutionary political forces loathed each other more than they did the Bolsheviks.

The main point is that Bolshevik Russia’s relations with West European countries were unfavorable due to its global revolutionary program for upheaval. Gábor Ujváry noted that the Germans were able to more easily settle their disputes with the Russians because the trade flows between the two nations were not nearly as large on the scale as with other countries. The Russians had been by then decimated and the crisis of 1923 in Germany was total: tens of thousands starved to death, which had not occurred there for ages. In addition, there were internal conflicts with the Kapp and Hitler coups, chaos reigned. In 1923 military French troops entered the Ruhr which ended in total defeat, Gábor Ujváry emphasized, as it was enough for the German Government to order the miners and public officers not to work, in exchange for which they would still receive their salaries. Not only were the French unable to procure provisions, they had to finance their needs wholly from their own resources.

László Gulyás felt that the issue was not winning or losing at Versailles, or who was to be blamed for the problems, but rather that the victorious allies were unable to work out a sensible peace treaty.

In 1815 the major European powers had been able to put an end to a 20-year-long series of wars, and the deal proved to be a success for 100 years. In contrast, the Treaty of Versailles made the conflicts permanent that carried within themselves the possibility of war. The ideal world with the League of Nations that Wilson envisioned proved to be nothing but a facade by 1922.

Zoltán Tefner quoted Henry Kissinger, the former American National Security Advisor as saying that the root of the problem liays in the fact that the politicians of the early 20th century were not of the same caliber as those of the previous century. They were far less talented and in general weak in character. Wilson, for instance, was easily offended, which is unacceptable for a politician.

Gábor Ujváry added that the greatest winner in the war still turned out to be the United States of America, not only economically and politically, but culturally as well, as it was able to urge the defeated nations to copy America and this was the point when Germany began to be Americanized. America’s exit from the European continent was executed on purpose.

László Gulyás added that America assumed its role not only as a power on the European stage but also as a global power that Roosevelt made clear to the participants of the London Conference in the autumn of 1932.

Concerning Rapallo, Zoltán Tefner stated that when Józef Pilsudski, the Polish Chief of State learned of the agreement between the Germans and the Soviets, he had a conniption fit. This could be considered a sort of precursor to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, as the commander-in-chief of the German Armed Forces considered a joint German-Soviet military action with Russia, the result of which would have included the annihilation of Poland, in spite of the fact that both the Soviet Union and Germany were completely exhausted at the time.

At the same time there exists false myth of the Polish-Hungarian friendship at that time, noted László Gulyás, because while Hungary had vested interest in the complete destruction of the Versailles treaties, Poland became the beneficiary of that same framework. If it hadn’t been for the Seven-Day War of January 1919, during the course of which Beneš succeeded in procuring part of Teschen, it would not have been unimaginable for Poland to have been incorporated into the Little Entente.

Let us add that it is even more interesting that after Turkey succeeded in compelling the revision of the Treaty of Sevres of 1920 (which meant that she retained at least the ethnic Turkish territories) and after the Treaty of Lausanne was signed in 1923, Kemal Ataturk’s political leadership became adherents of the new world order, Géza Gecse noted.

The Rapallo Agreement was signed by two countries on the brink of economic bankruptcy, Gábor Ujváry interjected, and he added that among Hungary’s neighbors all were hostile except for Austria, whose neutrality was not, however, benign. Only in 1927, when Itally’s political support was won, was there a tiny opening for revisionist politics. The Hungarian Revisionist League was formed also at the time.

Moreover, Miklós Kozma, director of the Hungarian Radio and Hungarian Telegram Office thought that the appearance of revisionist propaganda over the radio would endanger the ethnic Hungarians living as minorities outside Hungary’s borders, so this propaganda was totally absent from the Hungarian broadcast, Géza Gecse noted, which is why Kozma was so popular with one of the central propagandists of the Kádár regime, Ernő Lakatos.

Three decades on from the political transition the debate around the person of Miklós Horthy has yet to be settled. There are those who do not consider him a positive figure not only at the beginning but even during the World War II, including the re-annexation of territories, in which, with the exception of Subcarpathian Ruthenia, territories with majority Hungarian populations were rejoined to Hungary thereby rectifying much of the injustice of the Treaty of Trianon. As a result in 1941 Hungary had a population of 82% ethnic Hungarians while Hungarians still remained in Southern Transylvania and in Slovakia as well. What Horthy can be criticized for is the year of 1944, when a major proportion of the Jewish population was transported to concentration camps where they died, said Géza Gecse, although there is no proof of the Regent’s responsibility in that.

The phenomenon of passionate anti-horthy sentiments is evident not only among researchers in Hungary but also among those outside, noted László Gulyás. Catherine Horel in France, for instance, is unable to point to a single positive act by Horthy throughout his entire life and she casts doubt even on his accomplishments during World War I. László Gulyás believes that there are various phases of Horthy’s career, the end of which is undoubtedly that of the beginning of March 19, 1944, which is followed by the Holocaust. He referred to Gábor Ujváry as being able to expound on this topic with more authority than he himself, as Ujvári studied Bálint Hóman’s life which is judged in a similar vein in great detail.

Hóman was not a head of state, Gábor Ujváry continued. He went on to say that March 19, 1944, similarly to the Soviet Republic of Hungary, was one of the lowest points in 20th century Hungarian history. Miklós Horthy’s decision not to resign, as the deposed prime minister Miklós Kállay had advised him to do, legitimized all that was to follow. If Horthy had resigned, he could have gone down in history as one of the great Hungarian statesmen.

But if he had resigned following March 19th, he would not have been able to give the command to colonel Ferenc Koszorús in July 1944, the result of which was that the Jewry of Budapest escaped the deportations, interjected Géza Gecse.

We don’t know what might have happened in that case, but it is not inconceivable that not only the deportation of the Jewish population of Budapest but also that of the countryside might not have taken place, i. e. that the deportation of Hungary’s Jews would not have taken place at all. Consequently, Gábor Ujváry stated that is why István Bethlen, Kunó Klebelsberg and with a bit of effort Pál Teleki can be counted amongst the great Hungarian statesmen from this era, but Horthy – not.

This was followed by a question and answer session.

(Below is a link where the folllowing part can be found – in Hungarian:)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0WMfMUG89cI(külső hivatkozás)

László Wolczyk was curious as to what would have happened if Hungary had refused to sign the Treaty of Trianon, and when had there been a window of opportunity in which the national boundaries outlined in that treaty might have been changed.

According to Gábor Ujváry there was a possibility for some sort of revision in November and December of 1918, but none following that point.

Although Mihály Károlyi was an inept politician it was a sensible idea to have ordered a surrender of all firearms as there were towns and villages in Hungary where the situation was really terrible. Károlyi was not a traitor: it was he who ordered the “No! No! Never!” revisionist propaganda posters from Ernő Jeges, which appeared on the streets by the end of December 1918.

No! No! Never!

Géza Gecse noted that Transylvania had been occupied by 20,000 Romanian soldiers in December 1919 and in January 1919, while the Romanian army was being continuously developed. Just to compare: in August 1916 the Romanian Army broke into Transylvania with 300,000 soldiers!.

László Gulyás stated that there are two opposing viewpoints concerning the Hungarian soldiers who returned home in late 1918. The one that they would have been willing to defend their country, the other is that they would not. It would be worth seriously examining this question, nor is it irrelevant which region we examine as in certain instances it is important in national politics, as to whether or not there was an attempt to bludgeon an ethnic Hungarian notary to death, and whether that attempt was successful.

Gábor Ujváry called to attention the fact that half of the units returning from the front were partly non-Hungarians and therefore it is questionable as to whether or not they could have been counted on to defend the Hungarian position.

Concerning the regular and irregular soldiers, László Gulyás noted that it is difficult to judge. What would one call the Ragged Guard for example? Pál Prónay was a non-commissioned officer serving in the Guard. It is also questionable whether he created the Banate of Leitha (Lajtabánság) by his own authority or whether there was cooperation with the Hungarian government in this, or perhaps he was simply slightly mad.

Zoltán Tefner stated that soldiers were spontaneously returning from the front-lines. It was somewhat strange that there were professional elements in recruiting for the Hungarian Red Army to which Gábor Ujváry noted that in fact these recruits had been forced to join the army. The central government was in charge of the allocation of resources and the government leaders stated that if the trade union members did not join the Red Army, not only they but also their families would starve to death.

As a result of a visit to the conference in Szeged on the interwar period in Hungary on November 25, 2019, we extended the deadline for short films until December 4, 2019.

In all 20 jury members (historians: Zoltán Tefner (Corvinus University), Géza Jeszenszky (former Minister of Foreign Affairs), Ferenc Pollmann (Museum of Military History), László Gulyás (University of Szeged), István Majoros (Professor Emeritus at ELTE University), Andor Bánsági (WW1 blogger), Dávid Ligeti (VERITAS Institute) Géza Gecse (Aspektus) and Péter Hevő (ELTE); cameramen: Nándor Kelecsényi (National Filmmaker’s Association) and János Liszi graphic; teachers: Balázs Lados, András Mészáros, János Csordás, and Éva Hutvágnerné Róth; organizers for the Aspektus team: Juliet Szabó and Zsolt Bánhegyi, former winners of our previous clip-competitions: Ágoston Sándor and Dávid Varga students; vice-president of Rákóczi Association: Balázs Tárnok) judged the entries for the clip competition and based on their ratings of the total submissions; 5 short clips were ranked in the first, second and third places in the following order.

The prizes were given to the winners also in the Kossuth Club on December 6, 2019.

First place went to the video entitled From Fehérgyarmat to Hiroshima/ Fehérgyarmattól – Hirosímáig/ the starting point of which is the introduction and description of a World War I memorial in the town of Fehérgyarmat in the county of Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg which was then followed by wartime newsreels depicting events on the war front. Simultaneously the film notes the fact that the war was fought on two fronts. Tanks and airplanes appear on-screen invoking the revolution in the machinery of the war. The film informs the viewer that one of the ancestors of the creator of the film, István Farkas, fought on the eastern front, and for that he was awarded a rank in the Order of Vitéz (a Hungarian order of merit which was founded in 1920) of which the filmmaker’s own grandfather relates in the clip. The short film notes that one of the consequences of World War I was Hitler’s rise to power in Germany and thus the Second World War was brought about from the First which the filmmaker demonstrates with a shot of the dropping of the bomb at Hiroshima.

Filmmaker: Sándor Molnár, a student at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Eötvös Loránd University.

To view the film, click on the link below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YH4id4Cd6I0(külső hivatkozás)

Second place was awarded to the short clip entitled War Enthusiasm in World War I/ Lelkesedés az első világháborúban/. In this clip, the filmmaker played the piano and used the melody as background music. She elaborated on the various forms of enthusiasm showed for the war at its outbreak, mainly in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, during the month following the assassination of Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo, and this is compared to that of Germany. The filmmaker employed a series of primarily postcards, maps, and other images to illustrate her film and she did the narration describing not only the content of the 1914 propaganda but also how it shifted.

Second place was awarded to the short clip entitled War Enthusiasm in World War I/ Lelkesedés az első világháborúban/. In this clip, the filmmaker played the piano and used the melody as background music. She elaborated on the various forms of enthusiasm showed for the war at its outbreak, mainly in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, during the month following the assassination of Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo, and this is compared to that of Germany. The filmmaker employed a series of primarily postcards, maps, and other images to illustrate her film and she did the narration describing not only the content of the 1914 propaganda but also how it shifted.

Filmmaker: Ágnes Vida, a student at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences of Eötvös Loránd University.

To view the film, click on the link below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2wLj0OE8Sgw(külső hivatkozás)

Because there was only a slight difference in the points awarded for the three clips following the first and second placing, the organizers decided to award 3 third-place prizes for the following 3 short films.

Amongst these, the piece submitted by the students of the Secondary School of Paks was somewhat of a surprise to the members of the jury. Entitled Students of the Secondary School at Paks on the decision of the Second Vienna Award of August 30, 1940/ A paksi gimnázium diákjai az 1940. augusztus 30-i II.bécsi döntésről és fogadtatásáról/. This short clip invoked the day of the Second Vienna Award of August 30, 1940, in which, due to the ruling by Italy and Germany, Northern Transylvania was returned to Hungary. Using contemporary music and photos of Paks the short film referred to the events of 1940 and, primarily with a few short dialogues, invoked the events of the Belvedere Palace in Vienna and how they were received by the Hungarian public and in particular Paks. At the end of the dialogue, the screen shows the area returned to Hungary. It is important to note that this was the most important territorial revision between 1938 and 1941 designed to correct the injustice of the Treaty of Trianon. The members of the jury noted that a major flaw of this submission was that it did not indicate anywhere the connection between the First World War and the Treaty of Trianon, or if the peace resulted from the war at all.

To view the film, click on the link below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjA8JbRyDRA(külső hivatkozás)

Filmmaker: students of the Secondary School of Paks. The award was received by Bátor Bagócsi.

Also placing third was the film produced by the Secondary School from Kecskemét entitled „Victim, Aid, Heroism/ Áldozat, segítség, hősiesség/” which uses as its starting point the state of the town around the time of World War I. Also using primarily still images: postcards, paintings, newspaper articles, and photos that show the town. The Russian attack on Felsőkomárnok (Vysny Komárnik), which had previously been part of Hungary but now is in present-day Slovakia, is highlighted. During this attack most of the small town, which was at the time populated primarily by Rusyns, was destroyed. During the war, the town of Kecskemét played a major role in reconstructing Felsőkomárnok (Vysny Komárnik), something which the small Rusyn town has commemorated on a plaque and which the town’s inhabitants remember to this day. The film also mentions the fact that residents of Kecskemét have visited the town.

Filmmaker: students of the Secondary School in Kecskemét.

József Károlyfalvi, history teacher and consultant for the group, received the prize.

To view the film, click on the link below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HihXpfYDG-I(külső hivatkozás)

The jury also awarded a third prize to the video entitled „Let us remember the heroes!/ Emlékezzünk a hősökre!/”. The filmmaker here used archive footing from World War I, then shows a few photos of Hungarian World War I memorials noting that memorials to the war began to be the erected in Hungary in 1917. This was ended with a long shot of the World War I memorial in Lovasberény, Fejér County. Afterwards photos and other documents make us understand how many residents of the small town took part in the war, how many of them perished or became prisoners of war, how badly the war affected the life of a small community for generations to come.

Filmmaker: Anett Dózsa, a student at the faculty of Arts and Sciences of Eötvös Loránd University.

To view the film, click on the link below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GcHYJUO0Mmk(külső hivatkozás)

Géza Gecse – Juliet Szabó – Lilli Csirpák